Value, Power, and Collapse: A Marxist Reading of the Techno-Financial Age

Disclaimer : The pessimism expressed in this essay is a lens, not a prophecy — a thought experiment meant to clarify, not paralyze. We still live in the most materially abundant, technologically advanced, and opportunity-rich period in human history. The same forces that disrupt may also liberate. Artificial intelligence, if harnessed wisely, has the potential to unlock an age of radical abundance, creativity, and autonomy.

For the past forty years, the bottom 90% have been systematically gutted by a machine called “tech.” Automation eliminated jobs, globalization outsourced them, Uberization atomized them, and finance devoured what was left. Technology — once a promise — became the architecture of dispossession. In the United States, the top 10% now control 67% of total wealth; the top 1% alone hold 34.7%. The bottom half of the population owns just 2.6%, and 36% of Americans have less than $100 in savings — a society one missed paycheck away from collapse. Warren Buffett said it without irony: “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.” Scott Galloway notes the punchline: the fastest-growing demographic in America is billionaires — 500 of them in 2013, 2,500 now.

This isn’t a bug. It’s the system working exactly as designed. Which is why it’s time to stop moralizing and start thinking like Karl Marx — not the cartoonish communist, but the brutal analyst of systems. Marx is not much about revolution; he’s about understanding how value is created, how it’s extracted, and how ideology is built to conceal it. Infrastructure shapes superstructure. The economy sculpts culture.

Winners of the Past Four Decades

The winners :

Wall Street: Bankers, hedge fund managers, private equity professionals, and traders who have thrived in a deregulated financial ecosystem, vividly portrayed since Oliver Stone's "Wall Street" (1987).

Silicon Valley: Early-stage employees, developers, and executives of GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft), startups, and gig-economy platforms like Uber. The superficial prosperity—symbolized by luxurious penthouses and expensive coffees—is starkly contrasted by the precarious employment conditions beneath.

Top Corporate Management & Consultants: C-suite executives and high-end consultants benefitting from corporate governance and strategic advice monopolies.

Regulated Professions: Doctors, lawyers, educators protected by institutional barriers, certifications, and regulatory complexity, securing their economic positions.

Online Entrepreneurs & Builders (since 2010): A new generation of online entrepreneurs and digital builders leveraged platforms like Stripe, Shopify, and Facebook Ads to rapidly scale profitable ventures. These digital-first entrepreneurs thrived by creating cash-flow-positive businesses, harnessing accessible digital tools to swiftly generate and compound wealth.

Marx Revisited – Polarization and its Temporary Mitigations

What we’re living through isn’t new — it’s the reappearance of Marx’s central thesis.

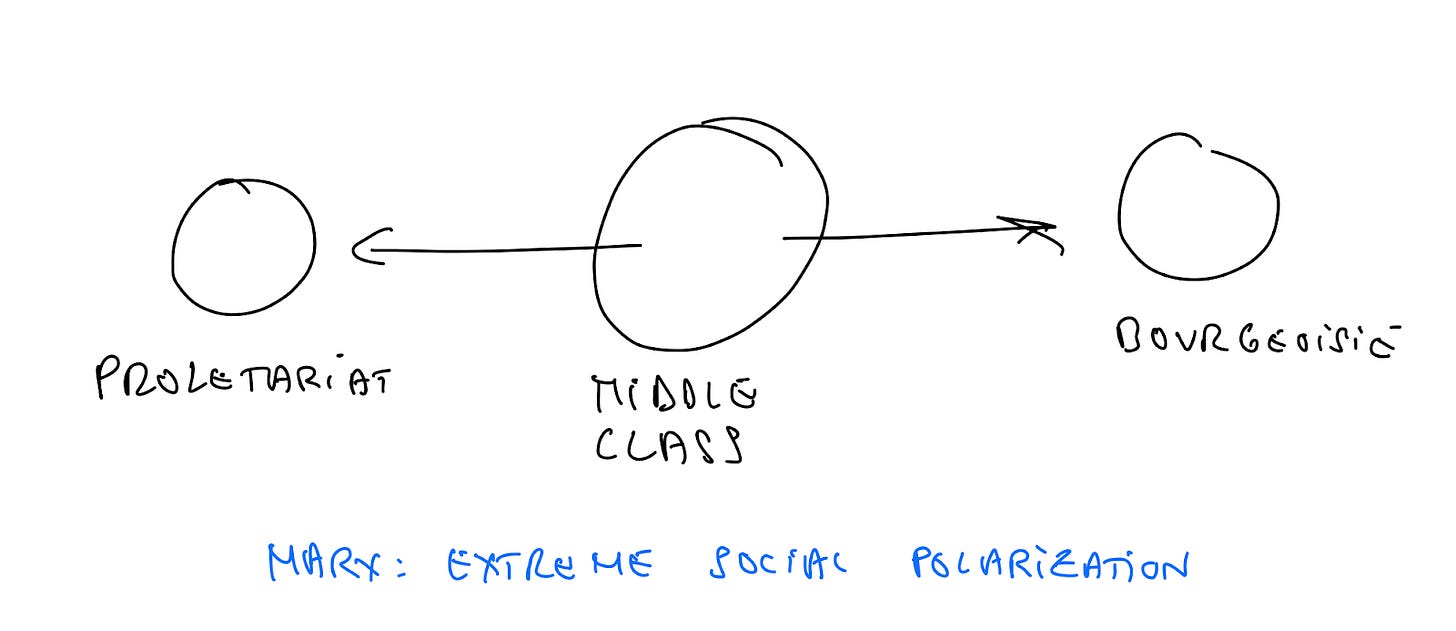

Marx was writing during the early rise of a fragile middle class — office clerks, civil servants, engineers, modest professionals — precariously positioned between capital and labor. These were the first mass consumers, frequenting places like Le Bon Marché in Paris, founded in 1852, the world’s first modern department store. Zola captured this shift in Au Bonheur des Dames (1883), where shopping became spectacle and desire was industrialized. Marx saw this class not as a stabilizer but as a buffer — easily seduced, easily crushed, and ultimately disposable.

Despite the rise of a middle class, Marx believed it would eventually dissolve under capitalism’s pressures, with most being pushed downward into the proletariat and a tiny minority consolidating into the bourgeoisie.

What remains is a raw binary: the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production (now digital, financial, and algorithmic), and the proletariat, who sell their labor into increasingly precarious, commoditized, and surveilled markets.

Marx called it the “industrial reserve army” — a permanently unemployed or underemployed class that keeps wages low and workers obedient. Capitalism requires this pressure, but it also contains a fatal contradiction: by suppressing wages and hollowing out demand, it undermines its own future.

Historically, we postponed the inevitable collapse with targeted injections of socialism — the 1884 Waldeck-Rousseau law legalizing unions in France, the 1886 American Federation of Labor, the New Deal from FD Roosevelt, welfare states, social security in post WWII Britain. These weren’t moral concessions; they were pressure valves and demand for the industry.

But by the late 20th century, neoliberalism replaced class warfare with debt warfare. Governments were convinced to borrow in order to fund welfare and avoid riots, while citizens themselves took on debt to maintain middle-class consumption habits. The result is grotesque: a system that subsidizes its own decay, while demanding austerity in the name of fiscal responsibility. It’s not sustainable — it’s anesthetic before amputation.

The Current War Against the Top 9%

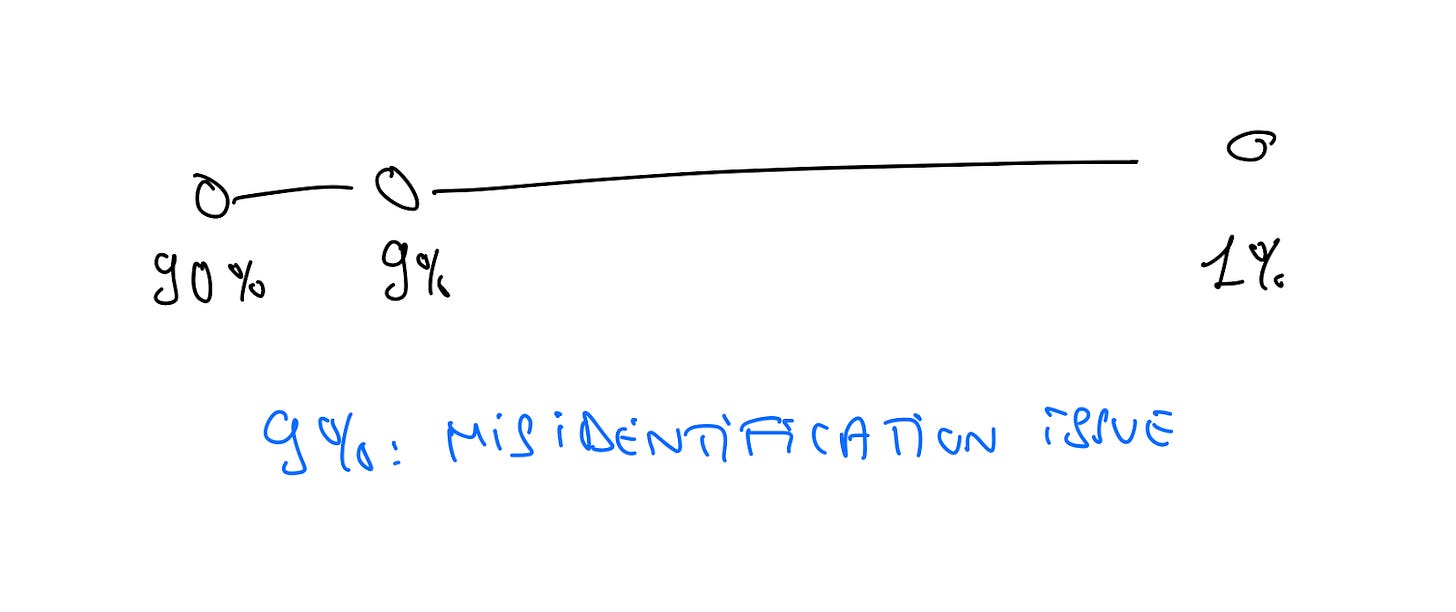

The top 9% thought they were safe. Earning $100k to $500k a year, with degrees, stock options, and gym memberships, they mistook proximity for power. They saw themselves as part of the elite, aligned with billionaires like Bernard Arnault — when in truth, they were just his consumers and his middle managers.

They didn’t own the system. They operated it. They fought in the class war, but not on their own behalf: they were foot soldiers deployed against the 90%, enforcing austerity, optimizing productivity, parroting meritocracy. But now the beast is turning on them too.

Musk fired 80% of Twitter’s staff and the company didn’t implode — it became profitable. That wasn’t a glitch. It was a demonstration. Investors took notes. Google employs 180,000 people with a median salary of $331,894. What happens when shareholders demand the same bloodletting? The logic is simple: the cost must come down, and the algorithm doesn’t care if you have a Stanford degree.

20th century demographer Alfred Sauvy called it the “déversement” — technological spillover from skilled to unskilled labor. But this time, the spill doesn’t go to humans. It goes to machines. In May 2025, TechCrunch reported that a quarter of Y Combinator startups had codebases almost entirely generated by AI. The new elite is not human. It’s a neural net. And it doesn’t ask for health insurance.

The Ripple Effect and Negative Trickle Down

The top 1% have exited the real economy. They don’t consume like the rest — they accumulate. Keynes called it the declining marginal propensity to consume: the richer you are, the less of your income you spend. At that level, money doesn’t circulate. It compounds.

And while the state pretends to govern them, they’ve already escaped the fiscal contract. They don’t pay taxes; they pay advisors. It’s the bottom 99% who will absorb the cost — through inflation, currency debasement, and the slow erosion of purchasing power.

The rich don’t fear democracy because it’s noble. They fear it because it works — and when it works, people vote to redistribute. Which is why the elite's true project is not profit, but insulation. But here’s the fatal flaw: by hoarding capital and crushing the middle class, they’re destroying their own customer base. Who buys the Louis Vuitton bags, the overpriced Paris apartments, the art, the Cartier watches, the illusion of luxury? If everyone else is broke or fired, the party ends. This is where Marx bites again — not as ideology, but as diagnosis. Capitalism, left to itself, will strangle its own demand. The engine keeps producing, but the passengers are dead. This isn’t trickle-down economics. It’s evaporation.

The Mirage of Innovation and the Anatomy of a Real Paradigm Shift

Economist Carlota Perez in Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital teaches us that capitalism doesn’t evolve gently — it mutates through violent, systemic shocks. Each technological revolution — from steam to silicon — follows the same arc: a burst of speculative frenzy as financial capital floods into a new technology, rising inequality and social tension as institutions lag behind, a crash that exposes the system’s rot, and, if society adapts, a deployment phase where productive capital builds something real.

But that transition depends entirely on the surrounding institutions. If they adapt and include, the result is a golden age. If they ossify or extract, the result is collapse masked as growth. After World War II, mass production met the welfare state — and the American middle class was born. After 2008, the internet met financialization — and the result was Amazonian empire and gig economy precarity. Nobel Prize Winners Acemoglu and Robinson (Why Nations Fail) made the line clear: inclusive institutions distribute power and compound prosperity; extractive ones centralize wealth and rot from within.

Web3 promised to be the next paradigm — a decentralized system of value creation, distribution, and ownership. The theory was elegant: protocols instead of platforms, code instead of CEOs, users as stakeholders. But so far, reality looks more like Pump.fun — a $600 million drain of liquidity from degenerate gamblers chasing meme coins. A new frontier, yes — but maybe one already colonized.

And yet, something endures beneath the casino: Bitcoin. Unyielding, permissionless, sovereign. If this is the turning point Perez predicted, and the empire of fiat is entering its terminal phase, Bitcoin isn’t just a hedge — it’s the ark.

From Zeitgeist to Weltanschauung: The Shift from Mimetism to Conviction

Here’s the only real (non marxist) advice left: make money, stack Bitcoin. Everything else is noise or cope. In a collapsing paradigm, capital is both shield and weapon. The question is how you generate it — and there are only two viable modes.

The first is Zeitgeist: ride the mimetic wave, imitate what works now, surf virality like a parasite with no spine. It’s fast, cynical, and often effective. Play the game, sell the dopamine, print the merch.

The second path is harder, but infinitely more powerful: Weltanschauung — build from conviction. Hold a worldview so sharp it cuts through consensus. Ask Peter Thiel’s heretical question: “What important truth do you believe that very few people agree with you on?” That’s where the alpha lives — not in following trends, but in anticipating reversals.

One path exploits the crowd. The other outsmarts it. Choose. But in both cases, the endgame is the same: exit the system, preserve optionality, accumulate non-state collateral. In short: make fiat, escape fiat.